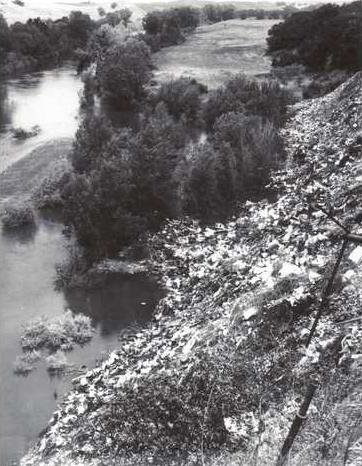

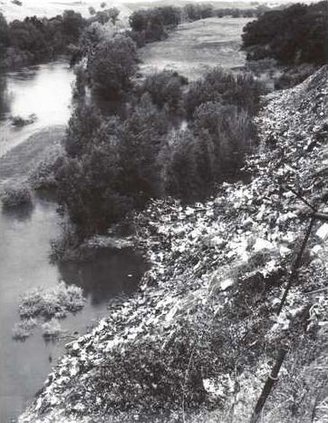

What is now a 25 acre neighborhood city park with meandering sidewalks and benches with views of the Stanislaus River and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range was at one time a municipal dump and trash burn site.

A half-century before Valley View Park at the top of Burchell Hill opened, on the same side of the Stanislaus River, below the seven-year-old sod and raised ravine, the City of Oakdale operated an open city dump, burning what it could and disposing incinerator ash and solids on 17 acres at the same location before the Stanislaus County Department of Public Health and State of California ordered the site to be closed down.

The Leader, with records requests to the City of Oakdale under the California Public Records Act, sifting through vintage news articles, interviews of current and former city employees and officials, and contacts with current residents as well as contacts with health organizations and health activists researched this conversion by the city to ascertain if any health or safety risks still exist.

History of the Site

From before 1932 to 1964, garbage and refuse, including solid and liquid wastes, such as paints, solvents, farm pesticides, sewage, and industrial sludge, were hauled in, sorted, salvaged and burned or buried. Some of the trash for many years was just pushed over the side of the ravine to the river.

A burn site operated at the dump over a four-decade span burning solid waste materials with no emission controls or restrictions on what was incinerated.

According to experts, air-blown lead particles often drop in the immediate vicinity of burn sites, but the toxic dust can travel for miles scattering in the nearby ground soil.

Before its closure, a 1963 Modesto Bee article on the burn site quoted then County Department of Health Director Dr. Robert Westphal stating, “This typical open burning site is responsible for smoke, odors, flies, rodents, water pollution, and rubbish accruing inside and outside the dump.”

A 1962 Oakdale Leader article about dumping procedures to prevent obstruction on the site, instructed dump users to, “unload over the bank into the riverside rather than the flatside” of the property.

Like many old dumpsites, the Oakdale City Dump had no liners to prevent groundwater contamination. It was operating during a time of few government regulations on waste disposal and open burning. Chemicals and carcinogenic toxins released at that time were many.

In 1963 Westphal urged immediate steps to close the dump for community health. In 1964 the county health department and state fish and game department shut down the dump citing sanitary and pollution procedures.

When the dump was closed, it still remained a dumping ground for ‘green waste’ and concrete. A new city dump opened near the airport on Wren Road near Sierra Road which later closed in 1972.

Park Proposal

As early as 1967, the City of Oakdale made plans on what to do with the former dump site located at the side of the river.

A May 18, 1967 news article reported that Oakdale Mayor Eldon Kitterman proposed to the parks and recreation department to form a plan for “Valley View Park” to be developed at the location. In 1977, the Oakdale City Council again heard proposals to develop the old dump site at the end of Valley View Drive and east of the water towers into a wildlife park.

In 1998 the city took serious steps in developing the park with the expected construction of the Burchell Hill housing tract. The city contracted with Kleinfelder Engineering of Stockton to conduct a “Limited Soil Sampling and Analysis” report.

Soil Report

The April 12, 1999 report documented evidence of burn waste still along the site and the embankment. Soil samplings revealed levels of dioxins, dioxin compounds, and arsenic that exceeded EPA guidelines for residential developments. Lead concentrations exceeded 10-times threshold concentration levels designated by the EPA. Beryllium concentration found in one area also exceeded residential limits.

Kleinfelder engineers recommended that the city continue to take samples along the downslope of the embankment and “The City should at a minimum…construct a soil cover over the entire burn dump. A fence and no trespassing signs should be constructed at the site perimeter.”

The report also noted that the city should include provisions to eliminate run-off into the Stanislaus River.

In an April 29, 1999 city council staff report, then City Administrator Bruce Bannerman wrote that the former dump site had been “pretty much cleaned up and abandoned” when it shut down. Bannerman also advised the council that the testing showed “usual conditions of an abandoned burn dump” noting the elevated chemical compound levels. Bannerman continued that Kleinfelder engineers “characterized the Oakdale dump as a ‘nice’ manageable problem” and the city’s plan for a park was an “ideal closure solution.”

Nowhere in the 19-page report or the supplemental 10-page appendix, however, was any documentation on the problem as “nice” or “manageable” or “an ideal closure solution.”

According to California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, even trace amounts of lead — particles so tiny they're barely visible — are enough to cause irreversible health problems in children who ingest or inhale them.

The Cornell University Department of Crop and Soil Sciences has stated there is no clear line of what is considered “safe.” If contaminant levels exceed agency guidelines or are higher than levels recommended by other sources, it is wise to reduce the exposure of children and adults. The university noted that it is particularly important to address any concerns about soil contaminants in areas where children play.

Preparation of Site

In response to a letter by then Planning Director, Steve Hallam for clarification so that the city could move forward with the park, Kleinfelder engineers provided three different courses of action for the city to take in regards to the elevated lead levels and other chemicals.

The first was to remove all of the below ground debris and transport it to a facility that would accept the waste. They cited the advantage to this procedure was that all the waste material would be removed. However, the cost factor was an issue, especially with the likelihood of more waste than expected being encountered. Also listed as disadvantages was the riverbank itself, with extra measures having to be taken to prevent debris from tumbling into the river.

The second recommendation was to attempt a “closure in place” by putting a “low hydraulic conductivity cap” or plastic membrane sheet on top of the debris area from the dump. The purpose of the cap is to keep pollutants contained and rainfall from passing through the debris that would carry contaminants into the groundwater. On top of the cover would be two feet of clean soil.

Advantages included that it was less costly, however there would be problems in anchoring the cap on the steep slope to the river as well as only a 30-year life span on the membrane requiring regular inspection.

A third option was to have additional and more extensive samples “with the hopes” of lower readings of the chemicals and lead.

While searching the city’s files, The Leader came across ‘Staff Notes” of a meeting with Doug Heard of Kleinfelder on the recommended choices with the handwritten notation, “Removing it is preferred option. Disintegrated waste for lead leaching and potential to contaminate ground water.” It is unknown who took the notes.

Retired Public Works Director John Word was the designated project manager of Valley View Park and the one who was liaison for the city and contractors, including Kleinfelder Engineering.

“We did nothing to hide anything,” said Word about the project. “There were no confidential reports about it. We provided everything.”

Word, a former 30-year veteran of the city public works department, said he would be “surprised” to learn there was soil contamination currently at the park.

Word recalled that two feet of top soil was put on the former dump site that was graded up from the developing housing tract. There was no cap called for when the final construction was done.

The city files also show an April 2000 memo by now retired Senior Engineer Technician Don Kirkham giving a historical perspective of the dumpsite with photos and news articles about its closing from the ‘60s.

When contacted, Kirkham said he provided the documents because the city seemed to have limited information about the site.

“They were bringing up trash when they were scarifying the site,” said Kirkham. “I don’t think the contractors knew it was a former dump.”

Kirkham’s statement seems to be supported with an October 2003 memo from the RRM design group. The memo to Hallam states that the soil on the site is “not appropriate” and that during excavating they were coming across debris and hitting subsoil that was not suitable for landscape areas.

Water Well 3 on Top of Dumpsite?

A few feet from the park, within the geographical range of the former dumpsite, lays City Water Well 3 which the city owns, maintains, and operates as a potable water distribution system to serve residents and businesses.

Also next to the former dump site is a 540,000 gallon concrete water tank, which was constructed at the time of the dump closing.

According to city records, the water well has been in existence since the 1930s.

Experts in the field state rainwater and precipitation can seep into the waste from abandoned dumpsites and carry chemicals to the groundwater below. The chemicals contaminating groundwater vary among dumpsites. But common contaminants found in groundwater are chlorinated solvents. Some of these solvents can pose a cancer risk at high exposure levels. When these chemicals reach private drinking water wells, it is common for levels to be of health concern. The closer a residential well is to a dump, the greater the risk of contamination. In some cases, contamination was found in drinking water wells more than a mile from a dump. In the case of Water Well 3, it sits on top of the abandoned site.

According to the city, a health risk analysis that followed the soil study showed that people’s health and the environment were not at risk even though on-site levels of lead in the soil were high. Ground water in this area is not contaminated according to the latest city reports.

No Methane Release or Recovery System

When contacted about the former city dump now a city park, Janice England of People Investigating Toxic Sites (PITS) stated that it was a nationwide issue of cities concealing dumpsites, only to later be made into parks, schools, and residential housing areas.

Since 1984, England and her organization, based in Southern California, have uncovered neighborhoods throughout the nation with reported cancer clusters and other serious illnesses to determine if illnesses were caused by chemicals in nearby landfills.

“It is shocking to have a well next to a former dumpsite,” said England. “The hazards to that are limitless.”

England stated that health studies have revealed connections between exposure to chemicals in dumpsites and cancer, leukemia, autism, respiratory illnesses, and birth defects.

England also said that despite cleanup efforts, carcinogenic chemicals and highly explosive, highly flammable landfill gases remain in many of these dumps.

England pointed out that the city should have taken steps to handle the release of landfill gasses from the covered trash. Methane can be generated for years after a landfill closes.

The more organic waste present in a landfill, the more landfill gas is produced by the bacteria during decomposition. The more chemicals disposed of in the landfill, the more likely non-methane organic compounds and other gases will be produced either through volatilization or chemical reactions.

Landfill gas is normally collected by either a passive or an active collection system. A typical collection system is composed of a series of gas collection wells placed throughout the former landfill. As gas is generated in the landfill, the collection wells offer preferred pathways for gas migration.

When contacted about the presence of a methane recovery system at the site, Word said the city felt there was no need since there was no longer any “wet garbage” at the former site and the number of years that had passed since its closure.

“Methane can migrate,” England said. “Houses sitting on concrete slabs are especially at risk.”

England explained that methane is a danger because the highly explosive, highly flammable gas can migrate underground through fissures in the earth at least 1,000 feet from the perimeter of the landfill. If the gases collect in nearby homes, sometimes forming pockets trapped beneath the slabs, the result could be an explosion or fire. If the gases contain carcinogenic chemicals, the residents’ health could also be jeopardized if the gasses seep through plumbing openings and electrical conduits in the foundation.

Residents

On a neighborhood canvass in the homes across from or adjacent to the park on Irvin Drive and Jacob Way, nine residents were contacted. Only one resident – a former city employee and longtime Oakdale resident – knew that a city dump had been in operation at the park site. The others had no idea and many expressed concerns that their yards might also be contaminated.

“I have three young children living here,” said one young mother on Jacob Way who did not want to be named. “This is really concerning. We walk right over there a lot.”

Rhonda Souza, 51, said she has lived in the house across the street from the park for over eight years.

“I was diagnosed with cancer last year,” said Souza. “I thought it was because I was a smoker. I wonder if the park had anything to do with it.”

None of the residents contacted knew if there was documentation on their closing papers about the former dump being located so close to their property.

The construction of municipal solid waste landfills has been regulated since 1991 by the EPA. Generally, the EPA requires that deed restrictions be put in place to prohibit the use of the landfill property and ground water when the property is sold, however in this case, the city converted city property to another city use – a park.

The EPA also does not notify residents of potential contamination based solely on the possibility that past industrial activities may have occurred.

With the latest turnover in the public works department, no officials for the City of Oakdale could comment if there was an immediate threat in Valley View Park or the Burchell Hill neighborhood. The only soil sampling results provided by the city from the information request were from 1999, even with asking for anything current.

The Center for City Park Excellence estimates that there may already be as many as 4,500 acres of landfill parks in major U.S. cities. As of now, children and adults continue to enjoy Valley View Park and its magnificent views, not knowing if Oakdale, in an innovating renovation, transformed a noxious liability into an attractive asset or took shortcuts and failed to take proper measures environmental experts say are essential at any former landfill.