Slavery as an institution has existed in almost every human society since Neolithic times. As the age-old process of buying and selling of humans as property for involuntary labor continues, slavery has been legally banned in every country of the world (Mauritania being the last to do it in 2007).

The United Nations definition of contemporary forms of slavery includes such conditions as forced labor, debt bondage, children working in slavery or slavery-like conditions, domestic servitude, sexual slavery and servile forms of marriage. The International Labor Organization estimates 21 million people worldwide are victims of forced labor, while the Walk Free Foundation, which produces the Global Slavery Index, estimates that 35.8 million people are in one form of slavery or another.

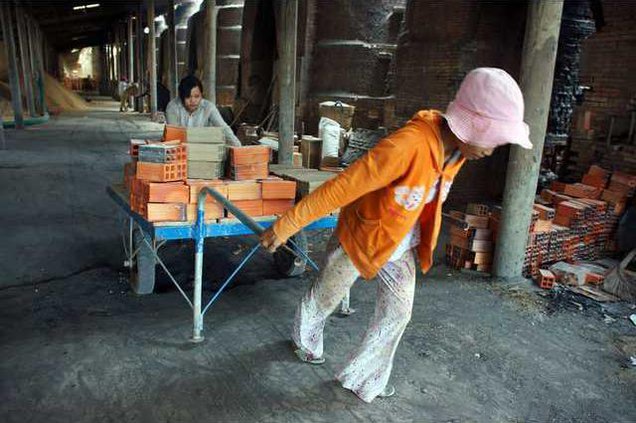

Forced labor is thought to be prevalent in Indias brick kilns, quarries and textile industries, while bonded labor is known to be common in China, Pakistan and Russia. Reports of rampant human trafficking in Thailands seafood industry made news last year, while an investigation by NGO Verit estimated a quarter of workers in Malaysias electronics sector were in forced labor.

The existence of modern slavery raises ethical and reputational concerns for global multinational firms seeking to buy products or engage in business with suppliers in countries with reputations for forced labor. As such, socially conscious firms, academics and policy-makers are looking for better ways to root out unethical practices in the supply chain. Recent research by Steve New at the Sad Business School, University of Oxford, suggests however that forced labor in the supply chain may not simply be a separate problem on the periphery, but rather an endemic feature of the existing socioeconomic system.

Recent busts of gangmasters and human traffickers supplying labor to the U.K. vegetable industry revealed the exploitation of migrants from Eastern Europe and, more significantly, the inadequacy of existing supply chain audit and certification procedures. Despite the passing of laws requiring firms to report their efforts to eradicate human trafficking and slavery from its supply chain in California, Australia and the U.K. the logic being that consumers could make more informed choices to exercise ethical shopping to shame firms into adopting better practices an analysis of the wider socioeconomic context that led to the emergence of forced labor in Cambridgeshire reveals a more fundamental issue.

Vegetable suppliers have reported a culture of fear and bullying exhibited by powerful supermarkets in transferring excessive risk and unexpected costs to the suppliers through various supply chain practices. Such aggressive behavior as levying extra charges, ignoring previous contracts and the delaying of payments by supermarkets has led to an asymmetry of power in the supply chain, and as a result, made the cheaper and compliant labor provided by gangmasters more attractive to suppliers. The fact that these large supermarkets had well-developed Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs points to a broken system in which firms enjoy a heroic moral stance by appearing to be working to reduce the problem while on the other hand, exercising brutal commercial power and hard negotiation on prices and trading terms that give rise to conditions favorable to forced labor.

What the world needs with respect to combatting forced labor in the supply chain is not just heroic rhetoric voiced by CSR programs. Nor do we need just vague policy statements produced by firms. Nor do we need just more melodramatic campaigns that present victimhood without mentioning the economic causes of forced labor. But we do need greater voluntary transparency in the supply chain that makes available specific data on firms products and how they are produced.

John Hoffmire is director of the Impact Bond Fund at Sad Business School at Oxford University and directs the Center on Business and Poverty at the Wisconsin School of Business at UW-Madison. He runs Progress Through Business, a nonprofit group promoting economic development. Heeje Yoo, Hoffmires colleague at Progress Through Business, did the research for this article.

The United Nations definition of contemporary forms of slavery includes such conditions as forced labor, debt bondage, children working in slavery or slavery-like conditions, domestic servitude, sexual slavery and servile forms of marriage. The International Labor Organization estimates 21 million people worldwide are victims of forced labor, while the Walk Free Foundation, which produces the Global Slavery Index, estimates that 35.8 million people are in one form of slavery or another.

Forced labor is thought to be prevalent in Indias brick kilns, quarries and textile industries, while bonded labor is known to be common in China, Pakistan and Russia. Reports of rampant human trafficking in Thailands seafood industry made news last year, while an investigation by NGO Verit estimated a quarter of workers in Malaysias electronics sector were in forced labor.

The existence of modern slavery raises ethical and reputational concerns for global multinational firms seeking to buy products or engage in business with suppliers in countries with reputations for forced labor. As such, socially conscious firms, academics and policy-makers are looking for better ways to root out unethical practices in the supply chain. Recent research by Steve New at the Sad Business School, University of Oxford, suggests however that forced labor in the supply chain may not simply be a separate problem on the periphery, but rather an endemic feature of the existing socioeconomic system.

Recent busts of gangmasters and human traffickers supplying labor to the U.K. vegetable industry revealed the exploitation of migrants from Eastern Europe and, more significantly, the inadequacy of existing supply chain audit and certification procedures. Despite the passing of laws requiring firms to report their efforts to eradicate human trafficking and slavery from its supply chain in California, Australia and the U.K. the logic being that consumers could make more informed choices to exercise ethical shopping to shame firms into adopting better practices an analysis of the wider socioeconomic context that led to the emergence of forced labor in Cambridgeshire reveals a more fundamental issue.

Vegetable suppliers have reported a culture of fear and bullying exhibited by powerful supermarkets in transferring excessive risk and unexpected costs to the suppliers through various supply chain practices. Such aggressive behavior as levying extra charges, ignoring previous contracts and the delaying of payments by supermarkets has led to an asymmetry of power in the supply chain, and as a result, made the cheaper and compliant labor provided by gangmasters more attractive to suppliers. The fact that these large supermarkets had well-developed Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs points to a broken system in which firms enjoy a heroic moral stance by appearing to be working to reduce the problem while on the other hand, exercising brutal commercial power and hard negotiation on prices and trading terms that give rise to conditions favorable to forced labor.

What the world needs with respect to combatting forced labor in the supply chain is not just heroic rhetoric voiced by CSR programs. Nor do we need just vague policy statements produced by firms. Nor do we need just more melodramatic campaigns that present victimhood without mentioning the economic causes of forced labor. But we do need greater voluntary transparency in the supply chain that makes available specific data on firms products and how they are produced.

John Hoffmire is director of the Impact Bond Fund at Sad Business School at Oxford University and directs the Center on Business and Poverty at the Wisconsin School of Business at UW-Madison. He runs Progress Through Business, a nonprofit group promoting economic development. Heeje Yoo, Hoffmires colleague at Progress Through Business, did the research for this article.