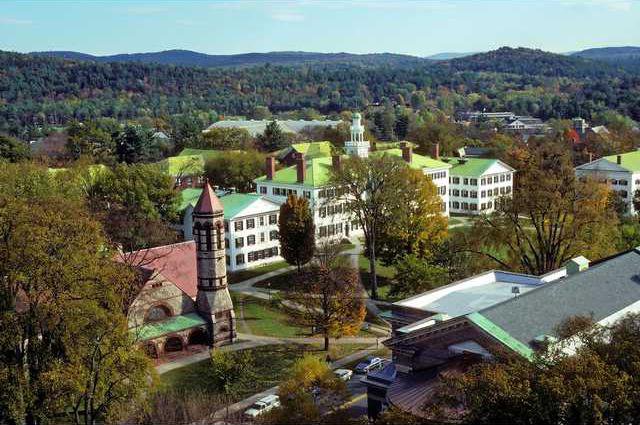

Len Greenhalgh is a senior management professor at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth in Hanover, New Hampshire. He is also faculty director of Tucks extensive programs for minorities, entrepreneurial women and Native Americans. Dartmouth College was founded in 1769 with a royal charter to serve Native Americans and European settlers in New England. The colleges emphasis on diversity and inclusion has continued ever since.

Greenhalgh took a faculty position at Dartmouth in 1978, soon after the upheavals of the U.S. civil rights movement and the ensuing efforts to help women gain a stronger foothold in education and the workplace. The Tuck School began serving minority entrepreneurs in 1980 to foster economic progress in communities that had faced historical discrimination. Greenhalgh taught in the inaugural class.

Tucks one-week intensive learning experiences for minorities are specifically tailored to this audience of entrepreneurs. They want to minimize time away from their businesses, so the programs pack a lot of learning into each day. Entrepreneurs tend to be good at tasks manufacturing products or providing services but they are less good at running the business. Greenhalgh focuses on the factors that most often get businesses in trouble: inadequate cash flows, lack of strategic direction, emphasis on efficiency and retaining valuable employees. Entrepreneurs tend to overemphasize dealing with everyday challenges and dont step back to see how the business is faring overall. So the one-week programs tend to be long-overdue strategic retreats for these enthusiastic business owners.

Greenhalgh adapted this program to the needs of women entrepreneurs in 2002. Prior to the time when there was greater emphasis on this, women hadnt been taken seriously as business owners and suppliers and tended to be excluded from management training opportunities. Yet Greenhalgh knew from his own research that women had a natural talent for running businesses. So with funding from IBM, Tuck partnered with WBENC the Womens Business Enterprise National Council to offer one-week strategic retreats for women business owners.

Native Americans posed a different challenge. An outcome of Americas history is that, as we all know, many Native Americans have had few advantages since their homelands were taken away from them and they were moved to reservations. The U.S. federal government provides some compensatory payments, but the reservations need to generate their own income streams to achieve economic independence, to create jobs and career paths, as well as to provide hope and positive role models for young Native Americans. Greenhalgh approached these challenges with a dual focus. Native-owned businesses need to be run well, just as do minority- and women-owned businesses; but attention must also be paid to the development of the tribal local economy.

Dartmouths emphasis on serving diverse populations turned out to be visionary. Minorities particularly Hispanics, African-Americans and Asian-Americans are growing as a proportion of the U.S. population and will outnumber European whites in the next 15 years. At the same time, womens roles are changing so that they will soon equal males in the educated workforce and the supply chains of Americas major industries. The Tuck School has decades of experience in serving these particular demographic groups and will lead the U.S. educational system in preparing these once-excluded entrepreneurs to take their place in the U.S. economy.

Other universities should create similar programs. There is so much money spent, as well as other resources, trying to compensate for an overall system (and I include a lack of individual initiative as part of the system) that does not meet the needs of minorities. Wouldnt it make a lot of sense to prioritize providing business education to members of the minority community?

John Hoffmire is director of the Impact Bond Fund at Sad Business School at Oxford University and directs the Center on Business and Poverty at the Wisconsin School of Business at UW-Madison. He runs Progress Through Business, a nonprofit group promoting economic development.

Greenhalgh took a faculty position at Dartmouth in 1978, soon after the upheavals of the U.S. civil rights movement and the ensuing efforts to help women gain a stronger foothold in education and the workplace. The Tuck School began serving minority entrepreneurs in 1980 to foster economic progress in communities that had faced historical discrimination. Greenhalgh taught in the inaugural class.

Tucks one-week intensive learning experiences for minorities are specifically tailored to this audience of entrepreneurs. They want to minimize time away from their businesses, so the programs pack a lot of learning into each day. Entrepreneurs tend to be good at tasks manufacturing products or providing services but they are less good at running the business. Greenhalgh focuses on the factors that most often get businesses in trouble: inadequate cash flows, lack of strategic direction, emphasis on efficiency and retaining valuable employees. Entrepreneurs tend to overemphasize dealing with everyday challenges and dont step back to see how the business is faring overall. So the one-week programs tend to be long-overdue strategic retreats for these enthusiastic business owners.

Greenhalgh adapted this program to the needs of women entrepreneurs in 2002. Prior to the time when there was greater emphasis on this, women hadnt been taken seriously as business owners and suppliers and tended to be excluded from management training opportunities. Yet Greenhalgh knew from his own research that women had a natural talent for running businesses. So with funding from IBM, Tuck partnered with WBENC the Womens Business Enterprise National Council to offer one-week strategic retreats for women business owners.

Native Americans posed a different challenge. An outcome of Americas history is that, as we all know, many Native Americans have had few advantages since their homelands were taken away from them and they were moved to reservations. The U.S. federal government provides some compensatory payments, but the reservations need to generate their own income streams to achieve economic independence, to create jobs and career paths, as well as to provide hope and positive role models for young Native Americans. Greenhalgh approached these challenges with a dual focus. Native-owned businesses need to be run well, just as do minority- and women-owned businesses; but attention must also be paid to the development of the tribal local economy.

Dartmouths emphasis on serving diverse populations turned out to be visionary. Minorities particularly Hispanics, African-Americans and Asian-Americans are growing as a proportion of the U.S. population and will outnumber European whites in the next 15 years. At the same time, womens roles are changing so that they will soon equal males in the educated workforce and the supply chains of Americas major industries. The Tuck School has decades of experience in serving these particular demographic groups and will lead the U.S. educational system in preparing these once-excluded entrepreneurs to take their place in the U.S. economy.

Other universities should create similar programs. There is so much money spent, as well as other resources, trying to compensate for an overall system (and I include a lack of individual initiative as part of the system) that does not meet the needs of minorities. Wouldnt it make a lot of sense to prioritize providing business education to members of the minority community?

John Hoffmire is director of the Impact Bond Fund at Sad Business School at Oxford University and directs the Center on Business and Poverty at the Wisconsin School of Business at UW-Madison. He runs Progress Through Business, a nonprofit group promoting economic development.